Flying Cars, VR and Dog Food

The INDG manual of style considers ‘mind-bogglingly’ to be in good style as opposed to ‘awesome’ or ‘cutting-edge’. So here’s one: flying cars — what a mind-bogglingly stupid idea!

In the world where a personal fuel-less aircraft has just circumnavigated the globe, humanity still expects to fly a thing designed specifically not to fly. Some visionaries may even praise this kind of thinking, bringing countercultural bohemian attitudes into the domain of industrial design. The very same people, I suspect, who once decided that dog toys should look like steaks and bones, with a view to constantly and morbidly torture beloved pets with gastronomical opportunities lost.

Still, those lovers of liberty are easy enough to debunk. If inconsistencies are to be approved of, how about a plane that can’t fly? We can even make it luxurious, a convertible maybe, available in a range of colours from ‘dangerous red’ to ‘provoking pink’. But you know what? I doubt it. I doubt that we’ll watch Vin Diesel drifting his Airbus Camaro down the roads of New York any time soon.

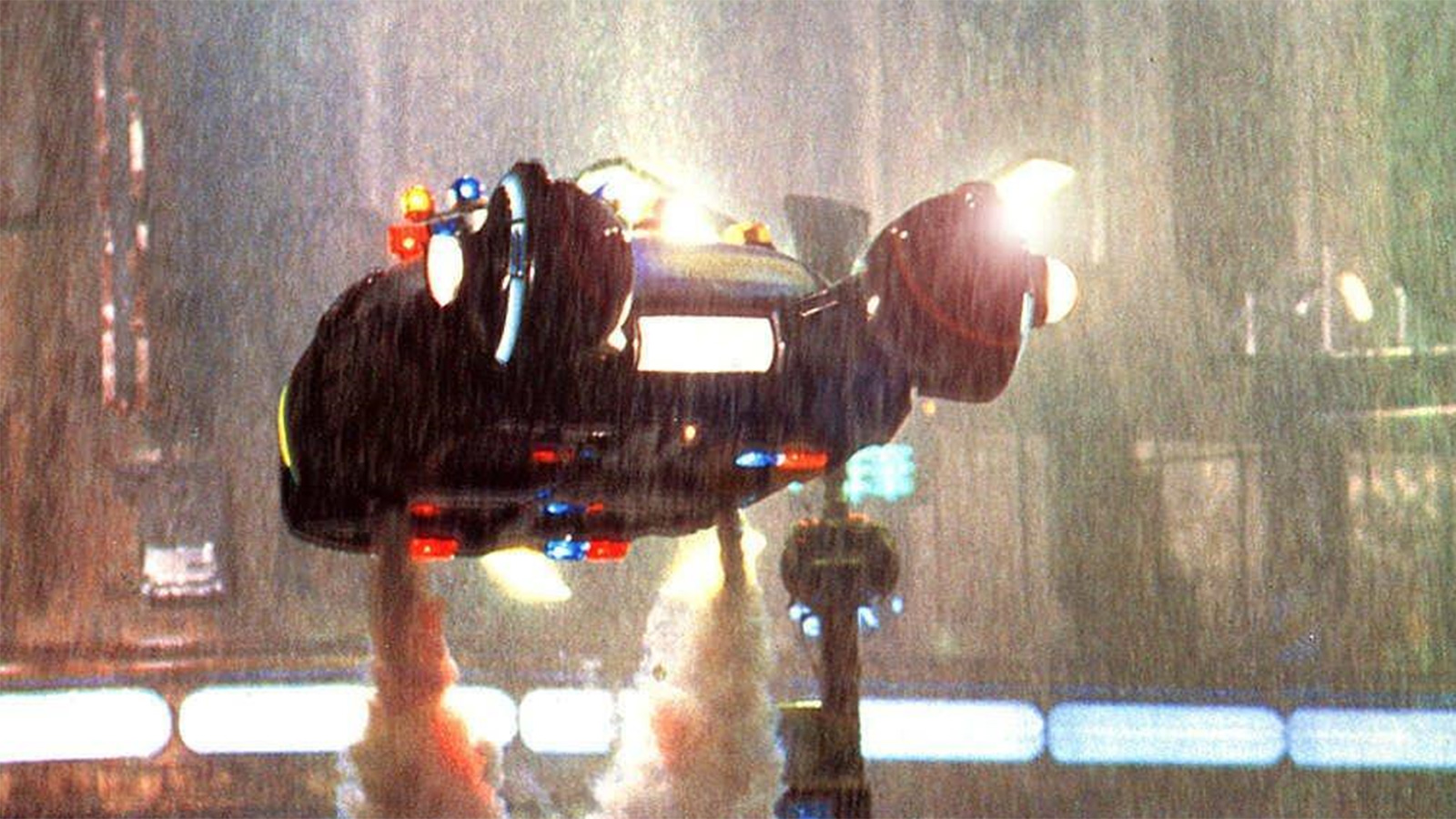

But imagine this: an elonmusque girl bursts into your office with a working hovercar prototype and all she needs for mass production is a humble hundred mil. Would you do it? I know I would. And rightfully so — everybody is going to buy a flying car. As a design object it’s worthless, but invaluable as a design archetype.

A hovercar is a thing every human being knows and loves, even though it’s nonexistent. And since designers are humans, too, — despite all evidence to the contrary — this thing ought to be designed and will be designed. Actual attempts to build one by none other than Ford date back to 1958. But it seems that archetypal design, i.e. producing preposterous things which everybody wants, is now being looked down upon, obscured by more pragmatical, goal-driven paradigms.

Too bad. Because archetypal design is arguably something that drives forward emergent technology, specifically virtual reality (VR).

VR is not by far new, but all we see is virtual cinemas, game arcades and Google Streetview. Can’t you go to a cinema or, well, view streets un-aided? Where is the mind-boggling stuff? Marc Hauser, an evolutionary biologist, may have an answer.

In 1999, he published an article in Nature called ‘The possibility of impossible cultures’. He starts with posing a question of whether all imaginable animals could, theoretically, evolve if Earth were a bit different. The answer is probably no. There are certain gaps, as he calls it — impossible physiological combinations. He goes on to expand this idea to language, music and so on.

And so, there is art we, as human beings, can’t even imagine. Even if this ‘impossible’ art could be generated by a machine not bound by our mental restrictions, it would probably ‘rapidly die out because it is unlearnable or learned with great difficulty’.

Hypothetically, VR spaces could be anything. In practice, we are stuck with familiar images like cinemas, streets and game arcades. Computer games created for or ported into VR don’t provide new images at all. Your typical fantasy game is an interactive variation of stories deeply rooted in human culture. In fact, Vladimir Propp claimed that that there were just 31 possible plots for a fairy tale (Morphology of the Folk Tale, pdf).

If you believe Hauser and Propp, the hunt for the new is doomed from square one. One will do better looking for the old, or, to be more accurate, the new in the old.

In this light, a VR office, where people from around the world could meet and work together in a second-life kind of setup seems like an implementation of a very old thought, ‘I’d like to spend less time commuting’.

Even a dystopian dream in which all our houses will be furnished with white objects and the actual interior will be overlaid via a VR headset which everyone in the apartment will always wear — even this dark future is nothing more, I think, than a realisation of the idea behind IKEA delivery service. Everybody wants their house furnished quickly, affordably and beautifully.

Creating a relation with an older concept or category is what many a marketeer would say we should do when designing for the future. Categories are not created equal, though.

One could say that a bike demo in a VR garage is connected to known concepts of ‘bike’ and ‘garage’. This wouldn’t be as productive, however, as trying to think about ‘speed’ or ‘beauty of tech’.

The ‘new’ has to go. Good riddance. Battle For Avengers Tower, one of the coolest VR apps in this author’s opinion, is described by its creators as an ‘incredibly innovative approach’. It also says, ‘for Marvel fans, the dream is to be one of the team in the middle of the action’. As any seven-year-old Marvel fan will tell you, it’s not that hard. They do it every day. All you have to do is just use your imagination.

Framestore VR are right in saying that being one of the Avengers is a core desire. We should work and always try to work with core desires as well. One of our products is called PEX Player, PEX standing for ‘product experience’. But behind that name there’s a very simple core desire: before people buy stuff, they tinker with it. You can’t tinker with stuff via the web. So let’s make it possible.

We will apply this to VR. The design process behind VR is no longer linear re-creation of reality, it’s a three-act drama with a deep emotional core inside. So let’s see where this gets all of us in a couple of years.